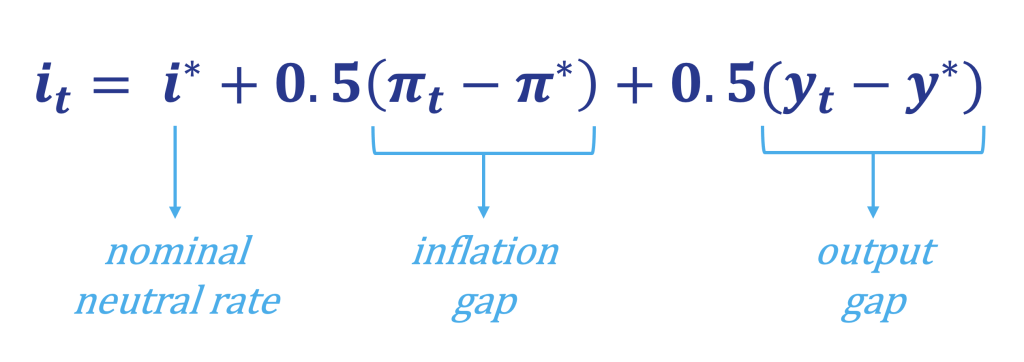

If you have ever taken a course in economics, chances are you’ve probably encountered this deceptively simple formula:

If you haven’t encountered it before, this formula is known as the Taylor rule – a basic framework designed to define the ideal level for interest rates based on economic conditions. It reflects the Federal Reserve’s dual mandate to promote maximum employment while maintaining price stability.

In a textbook world, the Taylor rule is a very simple exercise. Simply plug in a few key variables: the nominal neutral rate of interest (the rate at which monetary policy is neither expansionary nor contractionary), the output gap (the difference between actual and potential GDP), and the deviation of inflation from its target. The result? An A+ on your exam and a perfect estimate for future interest rates.

However, we don’t live in a textbook world. For starters, the inputs are never as clearly fixed as in a classroom setting. What exactly is the ideal level of GDP and inflation, and what is the neutral rate of interest? These figures have been estimated using historical data, assumptions, and models, but consider that interest rates are typically adjusted in terms of 25 basis points, or just 0.25%, which means the precision of these estimates can significantly impact the output of the Taylor rule. In addition, the real neutral rate of interest has been historically estimated around 2%; however, Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell recently remarked that the “neutral level may now be higher than during the 2010s, reflecting changes in productivity, demographics, fiscal policy, and other factors.” This acknowledgment underscores the challenge of applying formulas to dynamics that may not be static.

Also, consider that the measures used in the Taylor rule are known as lagging indicators. In other words, any shifts in the state of the economy will already be underway before the impact is reflected in these measures. This delay introduces an additional layer of complexity that arises from the need to forecast future conditions instead of relying solely on historical data.

This is a vast oversimplification of the many questions weighing upon the members of the Federal Reserve, and the complexities are not lost on financial markets. Investors closely monitor the Fed’s language, decisions, and even tone, trying to infer future policy moves. Throughout this calendar year, we’ve seen dramatic shifts in market expectations for the federal funds rate, reflecting both economic uncertainty and the evolving sentiment of the Federal Reserve. At Cornerstone, we’ve observed similar uncertainty and shifting expectations among our clients, from non-profits and corporations to individual investors.

One key takeaway is that, despite the noise, markets have remained surprisingly resilient. Headlines change daily, forecasts fluctuate, and yet the financial system continues to function. That said, volatility can test the depth and durability of markets. Every trade has two sides, and sharp swings in either direction can expose vulnerabilities. Liquidity, for instance, is often mispriced – undervalued in bullish markets and overvalued in bearish ones. Therefore, we remind investors of the importance of controlling the controllables within their portfolios – things like risk exposure, diversification, and cash availability.

We live in a world that loves measurable inputs and outcomes. All you must do is turn on a football game to see how likely (or better yet, unlikely!) it was for a spectacular catch to occur –right down to the decimal point. Baseball broadcasts highlight the improbability of a hit turning into a home run. Analytics have, no doubt, revolutionized the way sports are played and have unlocked new strategies and a world of new insights. Yet, the overemphasis of these measures, and the portrayal of perfect precision where it perhaps does not exist, can lead us to overlook the human element that brings about the unexpected.

Economics is called a social science for a reason. It is grounded in data but shaped by human behavior. As much as we need metrics to frame our thinking, expectations, and decisions, there is an element of the unknown that drives markets. This unknown continues to necessitate qualitative analysis, no different in the esoteric world of monetary policy than in the world of sports. In this light, the Taylor rule is not a prescription but a guidepost that we can use to frame monetary policy decisions, all while understanding that though the formula is simple, its application is anything but.